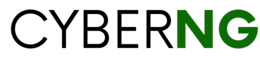

Tribal marks are a significant and fairly common aspect of cultural identity in Nigeria and Africa (and in other places across the world). It is classified as part of cultural heritage. Thus, it is still practiced in some parts of Nigeria (especially amongst the Yoruba people of southwest Nigeria). However, Nigerian tribal marks are not as prevalent as it was in years gone. As more Nigerians continue to acquire education, they have become averse to the practice for many reasons.

Tribal (or scarification) marks are vivid, permanent cuts or incisions made on parts of the body with razors or knives – particularly on the face. During the process, native dye made out of charcoal is often rubbed into the open incision. The native dye is applied to stop bleeding, and prevent the mark from closing up while the skin heals. Tribal marks are typically passed down the family line to members. They are also used to identify members of a particular tribe, community, or social status/class (such as members of a royal family).

Origin of Nigerian Tribal Marks

Nigerian tribal marks have existed for many centuries, and several ethnic tribes have their own unique marks. However, historians point out that Nigerian tribal marks became more widely used during the pre-colonial era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. It was a period marked by a series of inter-tribal wars that took place across West Africa between the 16th and 19th Centuries. A notable example was the ethnic strife between the Oyo Empire and the Ijebu Kingdom.

During that time, thousands of people – men, women, and children, were captured and sold into slavery by enemy tribes. The trans-Atlantic slave trade boomed along the coasts of West Africa; and several souls were taken in random places without trace. For that reason, family members began to apply tribal marks on their faces (and that of their children). The aim is to be able to identify or recognize family members who may possibly return or escape from slavery.

Nigerian tribal marks are clearly visible on body parts such as the forehead, cheeks, temples, and the chin. They may also be vertical, horizontal, or curved lines; or even other patterns. Majority of Nigerian ethnic tribes have their own distinct tribal marks. However, they are not so commonly used amongst people of Igbo, Efik/Ibibio, or Ijaw tribes. Nevertheless, there are a few exceptions amongst the southeast and south-south tribes. Such marks are often on their temples (in very few cases, on the cheeks).

Uses and Significance of Tribal Marks

Nigerian tribal marks (just as is practiced elsewhere across Africa) perform a number of functions which include the following.

Tribal, Family or Clan Identification

There are specific tribal marks used to identify each ethnic tribe, family, or clan (within the same tribe). Thus, they can easily identify one another with these tribal marks, anywhere they meet.

Beautification

In ancient times, it was popularly believed that tribal marks enhance the beauty of the bearer – whether man or woman.

Religious/Spiritual Purposes

In times gone, tribal marks were also used by many Nigerian tribes as a form of religious ritual. They could be used to ward off evil spirits from children. Or to stop a spirit child (ogbanje) from dying prematurely, or wandering aimlessly in the spirit realm. Tribal marks were also used to grant spiritual protection or power to a child.

For Healing

Though it lacks scientific proof, it was not uncommon for traditional healers to make incisions on children’s bodies (and faces) for healing purposes. Such tribal marks were applied on any part of the body deemed fit, and are often barely visible. They were used to treat diseases like pneumonia, measles, and convulsion in children.

The Legislation Against Tribal Marks in Nigeria

The practice of giving tribal marks to children and family members is fast dying out in Nigeria due to a number of reasons. Firstly, there is fear of possible viral (or other microbial) infection through contaminated blood and/or cutting instruments. The practitioners who carry out the cutting procedure often do so in septic conditions, or in environments where hygiene and safety is not guaranteed. For instance, HIV/AIDS infection is a big risk that many educated persons consciously yearn to avoid. Secondly, scarification inflicts pain on children; it may cause serious bleeding; and it is done without consent of the child.

To further restrict its practice, the Child Rights Act was enacted in 2003 by erstwhile Nigerian president, Olusegun Obasanjo. It was to the effect that:

‘No person shall tattoo or make a skin mark or cause any tattoo or skin mark to be made on a child’.

Any violation of this law attracts a fine of 5.000 Naira, or a jail term of one month, or both. In spite of this, some Yoruba families are still applying tribal marks as part of an enduring family heritage or ritual. This is common among practitioners of traditional (idol or ancestral) worship. According to them, every Yoruba child belongs to a patrilineal clan identifiable by a particular tribal mark, praise song (‘Oriki’), and other native identifiers.

Examples of Nigerian Tribal Marks

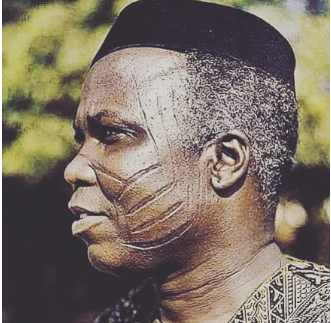

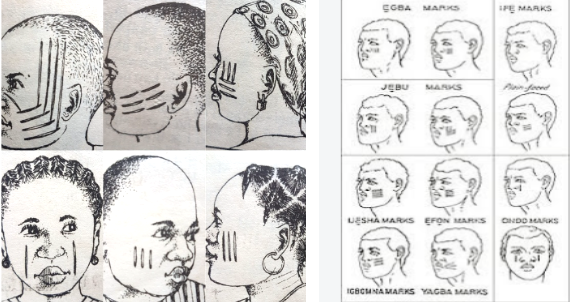

Tribal marks were particularly common amongst the Yoruba ethnic group of southwest Nigeria (but not limited to them). Here below are some of the well-known tribal marks in Nigeria.

Nupe Tribal Mark

The Nupe tribe of Kwara and Kogi states have a distinct set of curved marks on the cheeks. Otherwise, they use a single vertical mark on each cheek. These marks were used either to identify members of a particular family; for (spiritual) protection; or to show the social position/prestige of the bearer.

Pele

Pele is a generic tribal mark commonly used across Yorubaland. There are several versions of the Pele tribal mark unique to each Yoruba tribe. The typical Pele mark common amongst Ife people has three vertical lines drawn on each cheek. The single Pele is one vertical line on each cheek; it could be long or short. A long version of the single Pele called Soju, is commonly used by the Ondo people. There is also Pele Ijesha and Pele Ijebu.

Abaja (or Single Abaja)

Abaja is an iconic Yoruba tribal mark with several versions of it. It was an identifier for members of the noble families of Oyo Empire, but was later adopted by several Oyo people. It consists of three, four, or up to six horizontal lines on each cheek.

Double Abaja

This consists of two sets of horizontal lines across each cheek (in twos, three, or up to six lines).

Abaja Olowu

This is a distinctive tribal mark of the Owu tribe of Abeokuta (Ogun state). It is a set of three vertical lines drawn over three horizontal lines (on each cheek).

Gombo (or Keke)

Gombo is a combination of three vertical lines drawn at right angles to four or five horizontal lines on each cheek. A diagonal stroke across the left cheek, which starts from the nose, may be included. It is commonly amongst the Ogbomoso people of Oyo state, and the Egba people of Ogun state.

Jaju

Jaju is a single horizontal mark on each cheek. It is also quite common amongst the Ondo people.

Yagba Tribal Mark

The Yoruba tribe of Yagba (located further north of Yorubaland) makes use of three converging lines on each corner of the mouth.

Igbo Tribal mark

Tribal marks were not so common amongst the Igbo people. However, a typical Igbo tribal mark called Ichi was used to identify men with higher social status (or affluence). It was a single vertical line drawn on each temple (sides of the forehead). In other cases, they made use of incisions that appeared like solar discs on each cheek.

But over time, Igbo women acquired tribal marks either for beautification, healing, or identification purposes.